I have been blogging and using Twitter as a scientist since 2010. By that point it was pretty obvious that the internet was radically changing how scientists could engage with the public and each other, and thus science blogging had become quite popular. Like a lot of people, I wanted to write about how studies from my areas of expertise were reported in the media, and my first substantial blog post was about a large epidemiological study of homebirths in the UK. Twitter was a natural companion to blogging, since you could use it to share what you were writing. Eight years later I still blog and tweet. From time to time this comes up in conversation with colleagues, and they often ask if I really think it’s worth my time.

Twitter is a social network where users can share small messages with each other. It has two obvious uses: to promote things (like yourself, papers, and research projects); and to find things that you are interested in (like people, papers, and research projects).

Content discovery

A substantial part of our job as scientists is to know what is going on in our field. There are a number of traditional ways of doing this, which mostly revolve around reading lots of papers, participating in scientific societies, and going to lots of conferences. I suspect that once upon a time, well before I became a researcher, what got published or presented was a manageable body of the “best” research. However, the number of venues for research, and the number of researchers, even in highly focused areas, has grown considerably. Also, previous markers of quality, such as what journal something is published in, are now suspect. So where do you go to be exposed to the very best research in your field? Additionally, if you are like me and work across multiple areas (and don’t most of us do this to some degree?), there is no traditional way to keep up.

Twitter helps with this problem because you can choose to follow whom you want, and thus only see the content they are sharing. Thus, with a bit of work, you can turn your Twitter feed into a tool for finding important and interesting papers, workshops, tutorials, and so on. Thankfully, plenty of scientists see the value of sharing with each other, so it shouldn’t take long for a new user to find a few of them worth following. Examples that pop to mind are Mara Averick for all things #RStats, Anand Gururajan for animal neuroscience, and Marita Hennessey for child obesity and infant feeding. I try to do this as well, and you will often see me try to draw people’s attention to specific things.

Discussion

The content discovery facilitated by Twitter is enough to keep me logging in. However, Twitter really takes off once experts (and that includes you!) start discussing that content. In my opinion, this aspect of Twitter had gotten better in recent years, probably as the number of academics on Twitter has increased. I also see more efforts to help one another by asking and answering questions on Twitter. In fact, when I have a question about my research, I’m much more likely to “ask Twitter” than to send an email around my department looking for help.

In addition to the overall increase in the number of academics engaging on Twitter, I’ve also noticed an increase in the number of very senior people doing so, at least in my fields. I don’t think there were that many statisticians or epidemiologists active on Twitter five years ago, evidenced by the fact that I was a top search result for epidemiology despite being a complete unknown in that field. Thankfully this has changed, and now the rank-and-file such as myself can rub elbows with top epidemiologists such as (in no particular order!): Ken Rothman, George-Davey Smith, Maria Glymour, Miguel Hernan, Sandro Galea, Michael Oakes, Michelle Williams, Matthias Egger, Hazel Inskip, and Tim Lash, and so on. There are so many in fact that SER now keeps a running list.

The field of statistics is also blessed with a number of notable Twitter users, including Stephen Senn, Frank Harrell, David Spiegelhalter, Richard Morey, Kerry Hood, Jenny Bryan, Jeff Leek, Roger Peng, Regina Nuzzo, Deborah Mayo*, Rob J Hyndman, Rafael Irizarry, Brian Caffo and again, many others that I’ve missed. Medicine, psychology, neuroscience, and data science also seem to have plenty of senior researchers engaging on Twitter as well.

When I stop to think about it, the access that Twitter provides to these people just blows my mind. At this point I’ve been in dozens of conversations on Twitter with the very people whose papers and books I read - people that I’d be starstruck by if I bumped into them at a conference. To be clear, the majority of these people have no clue who I am outside of Twitter, and my CV isn’t nearly distinguished enough to demand their attention. I’m not saying this to be self-deprecating, but rather to encourage you to engage with them, because it’s absolutely one of the best parts of Twitter.

But what’s the value, really?

An example where this aspect of Twitter helped me was when I went from working as a statistical epidemiologist focused on infant growth, to my current role as a statistician collaborating on medical research. This meant trying to rapidly learn more about clinical trials and the regulatory environment they are conducted under, as well as clinical areas such as cardiology and oncology. So in addition to reading lots of books and papers, I also started paying more attention to statisticians (e.g. Stephen Senn, Frank Harrell, Andy Grieve, Kerry Hood, Tim Morris, and clinicians (e.g. Vinay Prasad and Darrel Francis) with lots of trial experience, to learn about the things that they thought were most important. I have not only learned tons by doing this, but have also gained confidence though my interactions with some of them.

Big topics

In addition to helping you find highly topical information about your field, there are broader scientific topics that come up on Twitter that I think are largely absent from the day-to-day experience of most researchers. Yet it’s these topics that are probably the most important ones for “us” to be having. These topics include science communications, open science, work-life balance, research integrity, reproducibility, and bias/discrimination in academia. Frankly, I’d feel a lot better about the direction of academia if I saw a few more Deans and VCs on Twitter talking about these things with the rest of us. Further, because scientists and academics are on Twitter discussing science and academia, it’s a great opportunity for people thinking about joining our profession (prospective PhD students, PhD students, early career researchers) to learn what it’s really about.

Social aspects

It’s very easy to become quite isolated as a researcher. Despite the fact I collaborate pretty widely as a statistician, most of my days are spent in front of a laptop. During a typical week, I’ll have several conversations with Brendan, one or two others with colleagues at the CRF, and say “Hello, how are you?” to a dozen people in my school. So I appreciate the purely social aspects of Twitter, and how my day can be lightened by a shared laugh with someone I don’t actually know but still consider to be a friend. Similarly, Twitter is also a great place to get congratulated, praised, supported, and consoled by your peers – things that simply don’t happen enough elsewhere. Twitter can even help you meet people before you go to a conference so you can make proper friends with them (special thanks to Jaime Miranda, Rob Aldridge, and Pete Etchelles for making that week in Anchorage more bearable for Mark and I).

I also like how Twitter keeps me connected with people I couldn’t otherwise stay in touch with, so I still get a sense of what they are up to. So I follow lots of Irish researchers, former classmates (shout-outs to Whitney Robinson, Lisa Q, Daniel Westreich, Tim Baird, Ashley Carse, Lisa Bodner, Beth Widen, Brie Turner-McGrievy, Shu Wen, Dan Taber), and colleagues from the lands I’ve left behind (e.g. Mark Gilthorpe, Kate Tilling). Otherwise, it’s out-of-sight, out-of-mind.

Finally, Twitter is great for professional networking. You might cringe at that word, the reality is that when it comes to hiring academics and researchers, employers can be risk averse. So Twitter not only allows you to connect to other scientists so you can be on their radar, it also gives you a chance to interact and demonstrate that you are the smart, reasonable, hard-working person that you are. Even better though, is that you can also connect with potential collaborators on Twitter, as I did with Bettina Ryll, who I am now working with in the area of patient engagement and education in clinical trial statistics and study design.

Risks

Life on Twitter is not without costs. Despite my opinion that Twitter is a net time-saver, there is no doubt that I have wasted plenty of time on it when I could have been doing something else. Because discussions happen in real time, I find it hard to walk away, since I don’t want to miss out. I can also confirm that those Likes and Retweets are as seductive as they are designed to be, and that I have spent a day on Twitter to keep checking how a blog-post I’ve shared is being received. With that in mind, it’s probably a good idea to set up some limits as to when you’ll check Twitter, and turn off things like push notifications.

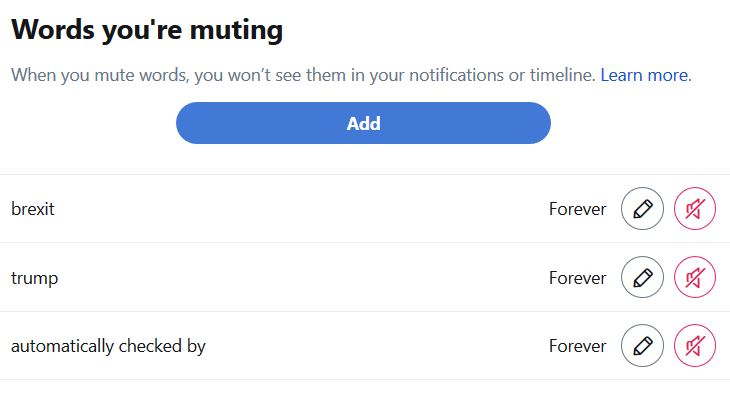

Another time-sink on Twitter is getting drawn into conversations on topics that aren’t exactly valuable for you as a scientist. Thankfully, by tweaking whom you follow, and possibly setting up a few filters, you can keep your feed on topic.

Trolls are another, related risk. The term troll is now used to refer to all kinds of abusive behavior, but in the good old days of internet message boards, it just referred to a person who enjoyed provoking other people into responding to their nonsense. Please know that these people still exist. You should never waste a single second on someone who doesn’t appear to be engaging in good faith. It is never worth it. The same goes for professional provocateurs. These are people spewing outrageous nonsense on Twitter purely to draw attention for marketing purposes. Please don’t take the bait, as any engagement, however righteous, just spreads their nonsense even farther. If you find there are certain people that you just can’t seem to ignore, just block or mute them and never think of them again.

We of course also need to be mindful of our own conduct on Twitter, especially since you can’t know how everyone on Twitter will perceive you. I’m not suggesting that everyone needs to be completely professional at all times, and I enjoy seeing the humanness of other scientists. However, I find it easy to fall into situations where I am being too confrontational or dismissive, and this isn’t a good look. On the flip side, it’s also very easy to misinterpret another person’s tone, so I think “assume best intentions” until you have clear evidence of the contrary is as useful on Twitter as it is with a 6-year-old. Life is too short for yelling at a computer screen over a misunderstanding.

The most important risk is the actual abuse that people experience, though this has never happened to me. The closest I’ve gotten (which wasn’t close at all) was after a post I wrote on sex-differences in tech fields, which then got picked up on Hacker News. It was a new experience for me to have something I wrote being discussed like this, particularly by an audience that included plenty of people that didn’t exactly agree with my views. I can admit that this made me feel a bit anxious at first. However, I didn’t receive any harassing emails, and only had to deal with a few rabble-rousers on Twitter, so I can only imagine the impact actual abuse has on other users. If you think that the things you post might attract abuse, you should probably seek advice on how to protect yourself.

Gaining followers

As I pointed out at the start, when you first use Twitter, you won’t have any followers, which can make “joining the conversation” challenging, particularly with people outside of your field who won’t recognize your name. To be clear, I do not care about followers for the sake of followers, it’s just that the social aspects of Twitter I find useful are amplified when you have some. Thankfully it’s not that hard to pick up several hundred fairly quickly.

First, I recommend that you Tweet as yourself, not on behalf of an institution or other brand. People like talking to other people, not anonymous buildings or logos. Next, use your profile to highlight evidence of your expertise and research interests. If I see a tweet I like (because it was retweeted or liked by someone I follow), I will often hover over the tweeters name to get a quick look at their profile. If what I see overlaps with my interests, I’ll then check out their feed and decide whether to follow them.

Once you are set, pick out a few dozen accounts that are specific to your field of research and follow them – and if you already know people from your field on Twitter, follow them and get them to follow you back. Start sharing relevant information, such as papers, blog-posts, workshops, and conferences. Importantly, you need to add value to your Tweets – such as throwing in an opinion, highlighting a key finding, or attaching the key plot or table. At the start you want a high signal to noise ratio, so no off-topic stuff.

Once you have your feet under you, don’t be afraid to engage with other experts. If you see a conversation already happening where you have an opinion and your expertise is relevant – jump in. If you Tweet Professor X’s most recent paper, make sure you include their Twitter handle. If you Tweet about a conference featuring several scientists on Twitter, include their handles in the tweet.

Twitter, like most things, will take a bit of effort on your part to get the most out of it, and if you do the stuff I just mentioned, you should be well on your way. I haven’t mentioned the best way to pick up followers though, which is to start producing content and sharing it, and blogging is a great way to do this.

Blogging

When I say blog (short for web-log), I just mean writing something and putting it online. The content can be anything (tutorials, critique, opinion) and the degree of formality varies.

The first thing that blogs are useful for is that they help you become a better writer. Many scientists don’t seem to realize that you became a professional writer the day you published your first scientific paper. Not only that, we get funding by writing people and asking for money. Now, as any writer will tell you, the best way to get better at writing is to write. So any time I finish a blog post, like this one, even if it’s not read by another person, I still got some practice writing.

Blogging also allows you to write for different purposes and audiences than you are used to. For example, writing lay-person summaries, something that is now often requested from funders, can be challenging for some who has only ever done scientific writing.

Blogs are great in that they allow for much faster publication than our traditional outlets. I have twice written blog posts that might have been written as editorials or letters, but I instead chose to put them on my blog (here and here). This meant they were “published” much faster than they would have been otherwise. Further, I was able to direct people’s attention to them on Twitter, including the authors I was responding to. Similarly, blogging allows for quick feedback that you can use to further improve your writing.

Another limitation of traditional publishing is that it rarely shows off the complete skill set of the researchers involved. Further, because we only tend to publish the end result of a study, early career researchers (who weren’t responsible for obtaining funding of the study) often need to wait a long time before their contributions actually appear on their CV. By blogging, early career people can build an online portfolio of their accomplishments and show off their skills. A lot of this won’t wind up on your CV, but it doesn’t mean that other scientists aren’t paying attention, or won’t consider it at hiring time.