Professors Nancy Krieger (NK) and George Davey Smith (GDS) recently published an editorial in the IJE titled The tale wagged by the DAG: broadening the scope of causal inference and explanation for epidemiology. In it, they argue that causal inference in epidemiology is dominated by an approach characterised by counterfactuals (or potential outcomes) and directed acyclic graphs (DAGs); and that this hegemony is limiting the scope of our field, and preventing us from adopting a more useful, pluralistic view of causality.

They began their editorial with the results of a literature search of [epidemiology AND causal AND inference]. They found 558 such articles, none of which were published before 1990, and half of which were published after 2010. I believe they were trying to show that causal inference is becoming a more important topic to epidemiologists. However, if that was the case, I think it makes more sense to ask how many papers mention causal inference out of the papers published in our field. After all, in epidemiology, it’s all about the denominators. Once you do this, a much more important problem appears.

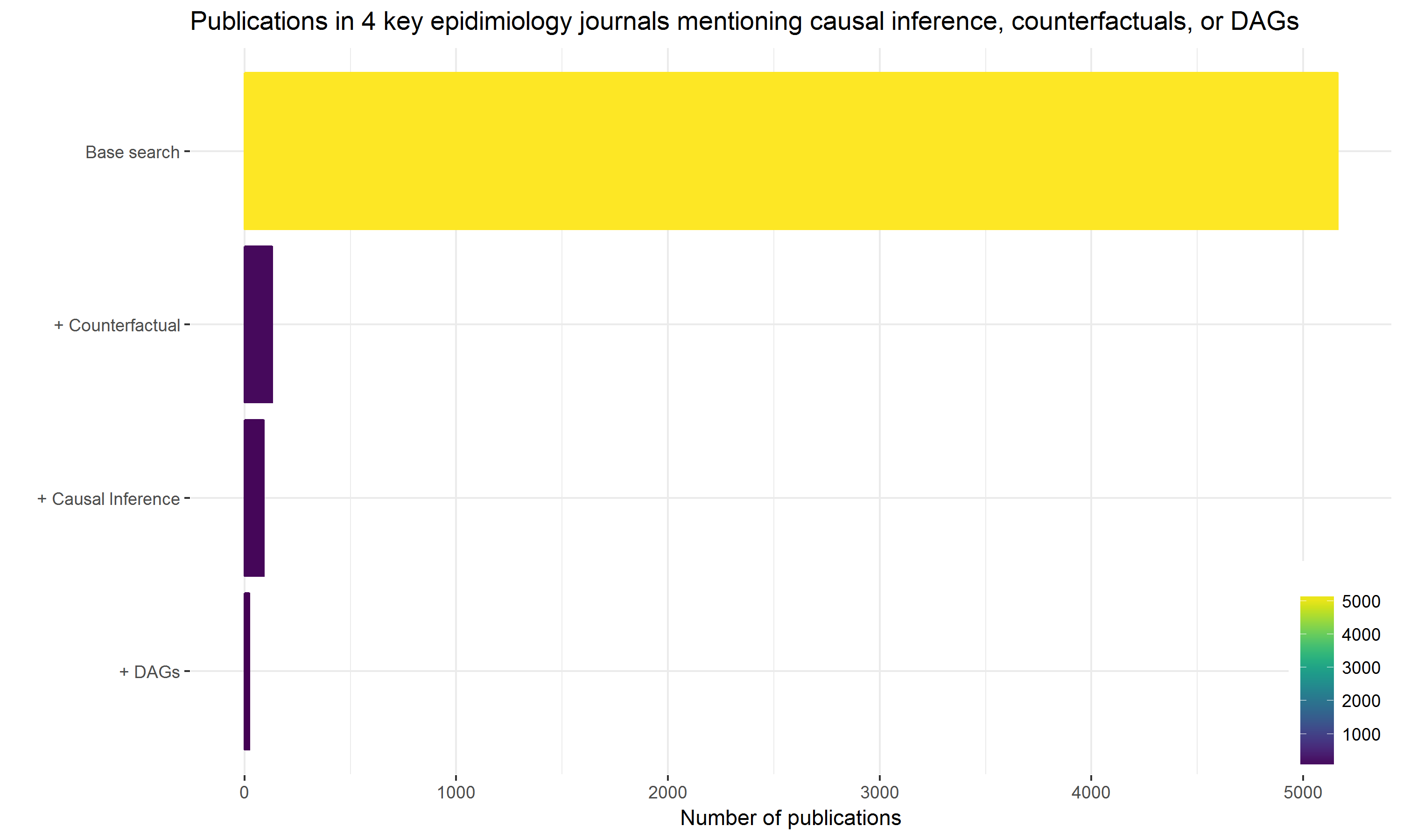

In contrast to their search, I started by looking for papers on Pubmed from the last five years that were published in the four key epidemiological journals where most of the discussion about causal inference probably takes place. These were: Epidemiology, the American Journal of Epidemiology, the International Journal of Epidemiology, and the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. Then, out of these papers, I alternately searched for those mentioning causal inference; those mentioning DAGs; and those mentioning counterfactuals. The results are plotted below.

Search 1: ("J Epidemiol Community Health" [journal] OR "Am J Epidemiol" [journal] OR "Int J Epidemiol" [journal] OR "Epidemiology" [journal])

Search 2: Search 1 AND "causal inference"

Search 3: Search 1 AND (causal graph* OR "DAGs" OR "DAG" OR directed acyclic graph*)

Search 4: Search 1 AND (counterfactual OR potential outcomes)

The plot of course supports NK and GDS’s assertion that counterfactuals and DAGs dominate our discussion of causal inference, but I am much more worried about how limited that discussion appears to be.

Like many others, I have previously argued that there is far too little causal thinking in epidemiology. The plot above is consistent with this view, and won’t allow me to accept that DAGs and counterfactuals are now pervasive enough to warrant some cautionary backlash. I instead believe that DAGs and counterfactuals, rather than displacing a more pluralistic view of causal inference, are actually creating the space for it to exist. Unfortunately, in an otherwise excellent and informative editorial, I think that NK and GDS misrepresent counterfactuals and DAGs, and worry that this might actually discourage their use. With that in mind, I offer the following commentary.

The story of a useful wrench, denigrated for not being a perfect hammer

Discussions of causal inference in epidemiology are often seen as “high-level”, or somehow beyond the rank-and-file epidemiologists. This is unfortunate, since drawing causal inferences from observational data is probably the biggest challenge we all regularly face. In my opinion, the single best way to help them meet this challenge is to teach them about counterfactuals and DAGs, which I have been doing for almost 10 years.

The most obvious value of DAGs for epidemiologists is that they facilitate a rigorous and transparent means of deciding which variables to adjust for when you hope to draw causal inferences from associations. They are especially helpfully for identifying tricky situations where adjustment for a possible confounder will actually create more bias than it resolves (e.g. collider bias).

Beyond this, DAGs can be used to describe competing sets of theory-based predictions that can be checked against data (Science!). They can be communicated unambiguously to others, so that disagreements about a DAG’s specific form can be debated and evaluated. DAGs can be used to describe most (if not all?) of the many biases researchers have identified, and re-identified, over the years. They are also helpful for contrasting study designs and the different assumptions they rely on (including Mendelian randomization, which I have never successfully described to anyone without using a DAG).

I could go on. I love DAGs, for all the reasons above and more. But the thing I love most about DAGs is that they encourage the exact kind of pluralistic causal thinking that NK and GDS advocate for in their editorial. For example, NK and GDS say the following about an approach to causal inference they admire, inference to the best explanation:

In brief, the essence of the IBE approach is to ‘think through inferential problems in causal rather than logical terms’ and to employ a ‘two-stage mechanism involving the generation of candidate hypotheses and then section among them’. IBE is thus driven by theory, substantive knowledge, and evidence, as opposed to being driven solely by logic or by probabilities.

When I read this, I thought it was a spot-on explanation of the kind of thinking DAGs facilitate. In fact, many of the other good ideas they shared were things that could be described and justified using counterfactuals and DAGs, including each of the things listed in Textbox 3. While reading their editorial, I couldn’t help feeling like NK and GDS weren’t giving DAGs the credit they deserve for promoting a deeper level of causal thinking.

The editorial also kept pointing out things that DAGs can’t be used for, but most of it was in a “no duh” kind of way. It was like warning me my car doesn’t drive under water. Strangely though, their key example of how DAGs go wrong was instead a perfect description of how they go right. It was the bit about the birth weight paradox.

To summarise, maternal smoking is associated with neonatal mortality, which won’t come as a surprise to anyone. However, if you only look at very low birth weight (VLBW) infants, there seems to be a protective effect, i.e. neonatal mortality is lower among infants born to moms who smoke. However, using a DAG, one can quite easily argue that because VLBW is a consequence of maternal smoking, stratifying by birth weights (which is what happens once we look at only the VLBW infants) leads to a collider bias. The collider bias in turn suggests the following: if you take a VLBW baby, and their mom didn’t smoke, then it’s more likely they were exposed to some other nasty insult that causes their VLBW, and that this alternate exposure was even more strongly associated with mortality. I teach this example every year. It’s great.

Seemingly dissatisfied with this conclusion, NK and GDS go on to say that an “elaborate and biologically plausible alternative explanation exists”. However, their explanation is 100% consistent with what others have suggested based on collider bias I just described. I quote:

It is that infants who are low-birthweight for reasons other than smoking may well have experienced harms during their fetal development unrelated to and much worse than those imposed by smoking…

They then note that their “proposed alternative biological explanation cannot be discerned from a DAG”, but also that “the DAGs for collider bias and for heterogeneity of LBW phenotypes have a similar structure.” I found this astounding, and can’t fathom why NK and GDS don’t see that they have the exact same structure. The only difference is that they have attached biologically informed labels to the nodes of the graph. Hence, while arguing the DAG is limited, they demonstrate that it actually worked as intended. It has described a causal structure that explains an otherwise paradoxical finding, to which they have added their own expert knowledge to further increase our belief that the DAG is correctly specified. This is how DAGs work. They are just a tool. They are not magical. Garbage-In-Garbage-Out applies.

Back to counterfactuals

Returning to the plot above, I fail to see how a counterfactual view of cause threatens to narrow the scope of our field, considering that just under 1% of papers from the best epidemiological journals even mention it. Further, I don’t see where NK and GDS offer any actual evidence of this occurring. What they offer instead is a more philosophical critique of counterfactuals.

They focus on a particularly “alarming feature” of counterfactualism, which is the idea that race or ethnicity can’t cause poor health (or anything else) because it isn’t intervenable. They then go onto to discuss that this “belief fails to acknowledge reams of genetic evidence demonstrating that H sapiens cannot be meaningfully parsed into discrete genetically distinct races…” They go on in this vein for some time.

I must admit, I had to re-read all of it several times before I could allow myself to conclude the following: NK and GDS aren’t just accusing counterfactualists of holding a debateable view of causality; they are accusing them of holding a deeply offensive and ignorant view of humanity.

So please let me be very clear. A counterfactual view of race doesn’t mean you think that there are “fixed races.” The counterfactual view of race doesn’t say race can’t be changed, or even that it exists. It doesn’t say that race is a “natural kind”. It doesn’t say we shouldn’t study it (and thus “narrow the scope” of our field). To me, the counterfactual view simply says that race can’t be the target of intervention. It says that race doesn’t cause poor health, racism does – which is the exact point NK and GDS get to at while arguing against the counterfactual view. I hope everyone can see the distinction, and nobody is put off of counterfactuals for fear of offending.

I would like to provide a less contentious example that I teach to my students, which will hopefully explain their value. Does fluoride prevent dental carries? This might seem like a straightforward causal question, but it is woefully incomplete without consideration of how we might vary exposure to fluoride. For example, we could fluoridate the water supply, dictate that manufacturers put more fluoride in toothpaste, or encourage people to brush their teeth more often. Each of these interventions represents a distinct causal question, with different sets of potential confounders, taking place at different scales, and all of them are more useful than simply asking whether fluoride prevents tooth decay. So counterfactuals are, at the very least, a useful fiction that I believe help crystalize causal questions. Even in situations where there is no possible intervention, due to ethical or other constraints, thinking about exposures as if you could intervene can be helpful.

In conclusion

A colleague once told me that Jamie Robbins, when asked what a confounder was, answered, “Whatever you need to adjust for to get the right answer.” I think this answer really gets to the point of DAGs and their counterfactual foundations. It’s not about identifying what A confounder is, but rather it’s about identifying the set of things to adjust for, given a specific causal question, asked in a specific context.

This is in stark contrast to what I see in most health research papers. The process of covariate selection, typically the crux of the entire analysis, is often omitted. When it isn’t, it can frequently be described as a monkey-see-monkey-do approach, or even worse, by some step-wise algorithm. Then, after dancing around the causal question at hand, careful not to admit their true motives, the authors are usually quick to practically apologize for their efforts with that old falsehood, “Correlation doesn’t imply causation.” All of this reflects a deficit of causal thinking that is a drag on our profession.

DAGs and counterfactual thinking are currently the best tools we have to counter this. Their value seems so obvious to me, but clearly not to everyone else. Every year, a student will inevitably ask, “If DAGs are so useful, why don’t epidemiologists use them?” I still don’t have a good answer for that question. It’s been about two decades since Robins, Greenland, Pearl, Hernan, Glymour and others helped to introduce DAGs to our field. It would be generous to describe their uptake as slow. There is no denying that most “successful” epidemiologists have gotten along just fine without them, and they rarely appear in the journal articles I read or review. So please forgive any defensiveness on my part; just know that we are on an uphill climb here.