I recently read a paper (via @yusunbin) in the American Journal of Public Health concluding (among other things) that “infants sharing a sleep surface” was a contributor to Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths (SUIDs; a classification that includes deaths due to SIDS, suffocation, or undetermined causes).

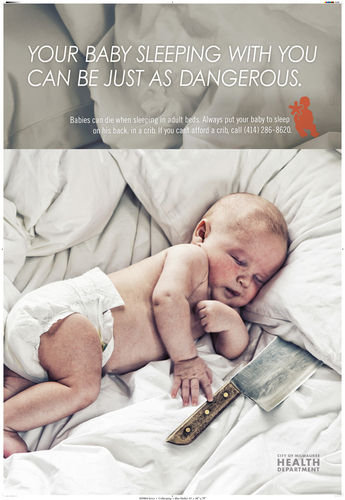

I was initially interested in the paper because, as a new parent, I know that the benefits and dangers of co-sleeping are hotly debated. On the one hand, there are well-meaning people that promote safe co-sleeping because it encourages breastfeeding (e.g. here). On the other hand, there are wide spread recommendations that parents should never, under any circumstances, share a bed with their infants due to SUIDs risk. A health department in the US felt so strongly about it they ran this public service ad:

The paper, Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths: Sleep Environment and Circumstances, aimed to contribute to this debate by describing the sleep circumstances of 3136 SUID cases registered in 9 US states between 2005 and 2008. The authors, however, have wrongly concluded that co-sleeping is a cause of SUIDs, given the data they presented.

In a public health context, we say that A causes B if we can intervene on A and expect some change in the probability of B occurring. For example, we could make cigarettes illegal, reducing the number of people who smoke, which in turn would result in fewer cases of lung cancer – because smoking is a cause of lung cancer. Identifying causes in epidemiology is a significant scientific challenge (e.g. whether smoking causes lung cancer is still debated by some), and we should only infer that one thing is a cause of another from strong evidence. This is because precious resources can be wasted intervening on things that don’t actually make people healthier; the public’s trust can be lost in the process; and because sometimes we want to impose an intervention on people that don’t want it (e.g. public smoking bans and helmet laws), which is an incredible responsibility. In other words, calling something a cause in the public health context is never trivial.

Keeping that in mind, here are some conclusions about the research in question:

From the paper’s abstract: “We identified modifiable sleep environment risk factors in a large proportion of the SUIDs assessed in this study. Our results make an important contribution to the mounting evidence that sleep environment hazards contribute to SUIDs”

The words risk factor, modifiable, and contribute suggest that a cause of SUIDs has been identified. Further, while the paper’s conclusions don’t explicitly say “Our research shows that bed sharing causes SUIDs,” they do seem to imply exactly that with the following:

“The American Academy of Pediatrics recently published expanded recommendations on safe infant sleep practices that include placing infants supine on a firm crib mattress without soft bedding or other objects in the crib; bed sharing during sleep is discouraged. Mitchell, going one step further, suggested that the most significant reductions in SUIDs would be achieved if the practice of infant bed sharing were eliminated. Despite these expert recommendations, challenges to reducing hazards in the infant sleep environment remain, as evidenced by infant sleep surveys documenting a continual increase in infant bed sharing in the United States since 1993. Future research should focus on development of novel interventions that facilitate behavior change and result in a safe infant sleep environment”

Further, this is from the AJPH press release: “Sleep environment hazards contribute largely to sudden unexpected infant deaths. Placing infants on their backs on a firm crib mattress without soft bedding or other objects in the crib as well as not practicing bed sharing with adults are key practices that help to prevent sudden unexpected infant deaths, a recent study from the American Journal of Public Health suggests.”

Again, clearly causal language on display here (contribute, prevent, not practicing).

Finally, the lead author, Patricia G. Schnitzer , is quoted in a University of Missouri press release: “The safest place for infants to sleep is on their backs in their own cribs without soft bedding.”

So clearly there are causal inferences being made, but are they based on reasonable evidence? My opinion is no, they are not.

The best way to evaluate whether one thing is a cause of another is a randomized controlled trial (RCT). In its simplest form, we would randomly divide a large group of people into two smaller groups, expose one group to the risk factor, and then look at the difference in the outome. For an outcome like death, we could compare the proportion of people who died (called the risk of death) in the exposed group to the proportion of people that died in the unexposed group. By comparing these risks (e.g. with a risk ratio, or a risk difference), we can make inferences about the causal effect of the exposure on the outcome.

However, there are many important research questions that cannot be studied with RCTs, usually due to ethical concerns, or practicability. When RCTs aren’t possible, we usually turn to case-control and cohort studies, which are both observational studies. In a case-control study, people who have already experienced the outcome are recruited, and their characteristics are compared to the characteristics of people for whom the outcome didn’t occur. In a cohort study, a sample of people who have not experienced the outcome are recruited, and then followed up until some of them experience the outcome, and the characteristics of the two resultant groups can be compared.

Regardless of which study design we use (RCT, case-control, or cohort), we are comparing groups of people to see if differences in the outcome coincide with differences in other factors. If we see that the outcome is correlated with the risk factor, we must then evaluate the potential for a causal explanation. In an RCT, the risk factor is randomly allocated, so the only way it could be correlated with the outcome is through a causal mechanism (which is why the RCT is the best form of causal evidence). Conversely, because the risk factor is not randomly allocated in a case-control or cohort study, it is possible that the correlation exists because the risk factor and the outcome share a cause. For example, grey hair is associated with arthritis, not because it is a cause, but because the two things are confounded by age. Thus, even in the best observational studies, the possibility of confounding by unknown or unmeasured factors can never be completely ruled out, which places severe limitations on our ability to make causal inferences.

All of that being said, the research in question used a case-only design, which is just a way of saying that there is no comparison group; and without a comparison group, there is no rational way to compare risks or infer causation. For example, this study found that among the 3136 cases of SUIDs they described, 64% were sharing a sleeping surface. That sounds bad. That sounds like sharing a sleeping surface must be a cause of SUIDs. But what if 64% of all infants shared a sleeping surface, including infants who never experience SUID (which is not an outrageous idea)? Then the risk of the exposed group would be the same as the risk in the unexposed group, and we would conclude that the exposure is not a cause of the outcome. The only possible way for a case-only design to identify a cause of the outcome would be if the suspected risk factor was known to be very rare in the population at large - and even then a more thorough study would be appropriate.

Furthermore, consider that 78% of the SUIDs cases died in the home. Is anyone suggesting that sleeping at home is a SUIDs risk? Of course not. Clearly a high prevalence of something in a sample of cases is not strong evidence of a causal relationship. Lastly, without a comparison group, we can’t assess the potential for confounding influences that might instead explain any correlation between co-sleeping and SUIDs, nor can we evaluate if there are other characteristics that make co-sleeping safer (possibly breastfeeding) or particularly unsafe (e.g. under the influence of alcohol).

Notably, the authors themselves acknowlege this in the following two statements:

“Furthermore, without access to a nonaffected comparison group, risk cannot be determined.”

“Although survey data are now available that describe usual infant sleep practices among living infants, the etiological component of infant sleep environment characteristics with respect to risk of SUIDs cannot be determined without an analytic study in which the sleep environment and other characteristics of infants who die suddenly and unexpectedly are compared with the same characteristics in living infants. Such an investigation is beyond the scope of the NCDR-CRS data.”

So how do they reconcile the causal inferences I previously outlined with these limitations in study design? Here is the first sentence from the paper’s conclusion:

“From a public health standpoint, it is not only important but at times more prudent to focus on prevention before etiology is definitively determined.”

My translation: Our study is in no way designed to support the conclusions we made, but the problem we are working on is so important that we really need to do something now, and not worry about the evidence.

While I agree that there could be circumstances that warrant public health action even in the absence of firm scientific evidence, the decision to act must include thoughtful consideration of the unintended consequences of the action, lest we do more harm than good. Unfortunately, there is no consideration of this in the paper. Even more problematic, the paper fails to cite any research that doesn’t agree with their conclusions, despite the fact that such conflicting evidence clearly exists (for example). The fact that this was published in AJPH, a highly influential journal for public health policy makers, makes this all the more troubling.